A Bump in the Road?

2023 began on a positive note. Prospects of a resilient economy and moderating inflation raised hopes for a soft landing and propelled stocks higher. Consumer spending was robust and GDP growth seemed to be in line with levels seen in a normal economy.

But much like the experience of the last several months, investor sentiment continued to fluctuate between extremes of optimism and pessimism. An exceptionally strong jobs report for January re-ignited fears that the economy may be running too hot for the Fed to pause. Bond yields rose sharply in February and stocks sold off as investors expected the Fed to continue tightening.

As eventful as the bear market has been so far, one of its momentous milestones took place in early March. It has been long feared that the rapid pace of monetary tightening would eventually lead to a financial accident and a subsequent crisis. Those fears came true as two regional banks, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank (SB), collapsed on March 10 and 12, respectively.

Bank failures are rare and they are almost unheard of outside of recessions. SVB and SB became the two largest banks to fail since the Global Financial Crisis. Their demise was swift as they unraveled in just a few business days. Fears of contagion spread across the globe and eventually claimed Credit Suisse a week later on March 19 as it was bought by UBS with assistance from the Swiss government.

We examine the short and long term implications of recent developments in our analysis.

At this stage, the banking crisis appears to be more of a bump in the road rather than a crippling pothole or crater.

Background

Let’s take a look at the macroeconomic backdrop that led to this recent bank crisis.

The massive stimulus put in place to fight off the pandemic led to a significant growth in bank deposits and loans. The large regional banks were at the forefront of this surge in loan growth. While their share of the total U.S. loan book was less than 20% in 2019, they accounted for almost 40% of subsequent loan growth. Deposits also grew more rapidly in comparison to their normal pre-Covid levels.

This rapid increase in bank balance sheets came about in an era of easy money and abundant liquidity. As we all know now, those factors also caused a sharp spike in inflation and abruptly triggered the most rapid monetary tightening cycle ever.

Regional banks are less regulated than the systemically important large banks. Their governance oversight, risk management practices and capital resilience eventually proved inadequate to withstand the dramatic rise in interest rates and the unprecedented speed of a run on deposits.

Here is a look at how this banking crisis may be different from previous ones and some of its short and long term implications.

Comparisons to 2008

How does the current banking crisis compare to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008? Will the events of March unleash a tidal wave of losses and bankruptcies and a deep global recession?

At this point, we do not believe that the current banking crisis will be nearly as severe or protracted as the GFC. Our optimism is based largely on the different origin of this crisis and the swift policy response that has limited its contagion so far.

Different Causes and Scope

Virtually all banking crises in the past can be traced to large loan losses stemming from bad credit. These losses typically arise from aggressive lending and poor underwriting. Borrowers turn out to be less creditworthy than believed and become progressively weaker as the crisis unfolds.

The transmission of a banking crisis into the broad economy follows a typical playbook. Loan losses diminish bank capital and inhibit the ability to lend in the future. The decline in loan growth then slows consumer spending and capital investments. The intensity and duration of this contagion eventually drives the depth of the ensuing recession.

However, the trigger for this banking crisis in March was not related to credit. It was instead a duration effect related to the rapid rise in interest rates. We know the basic bank business model is to borrow short and lend long. Bank deposits are short-term liabilities and bank loans are long-term assets. Bank balance sheets have an intrinsic duration mismatch where assets are more sensitive to interest rates than liabilities.

The rapid rise in interest rates triggered this duration risk and created unrealized losses in the long term bonds and loans within bank portfolios. The same rapid rise in rates also made money market funds at non-banks more attractive than bank deposits. Even as bank deposits were declining in a flight to money market funds, regional banks became vulnerable to another unusual risk.

Bank deposits are insured by the FDIC up to $250,000. Regional banks generally work more closely with small businesses. With a corporate clientele that typically maintains large balances, regional banks ended up with a high proportion of uninsured deposits in excess of $250,000.

Silicon Valley Bank catered predominantly to the venture capital community within its geographic reach. Given its client base, SVB ended up with one of the highest proportions of uninsured deposits among all banks at over 90%.

The decline of bank deposits at SVB was initially driven by the liquidity needs of its clientele as venture capital funding dried up. As SVB sold off assets and incurred losses to offset the initial decline in deposits, things quickly snowballed out of control as depositors feared for the safety of their remaining uninsured deposits.

In a brave new world of digital banking and social media, depositors pulled out a record $42 billion in deposits in one single day on March 9.

In an unprecedented bank run in terms of speed, SVB collapsed in two business days.

Unlike prior banking crises, this one was triggered by the unique confluence of a concentrated customer base in one single industry and geography, inadequate liquidity provisions and a lack of proactive regulatory oversight.

While a credit crunch may yet develop in the coming months, this banking crisis so far is different in that it has not seen large credit losses from defaults or bankruptcies. The SVB failure was not credit-driven, but rather a classic run on the bank created by a crisis of confidence and the ease of digital banking.

And finally, a quick word on the likely scope of this crisis in the coming months. This banking crisis is likely to be far less severe and systemic than the GFC because of one key difference – the health of the U.S. consumer.

The consumer, who drives 70% of the U.S. economy, is far more resilient today than was the case in 2008. The consumer balance sheet is healthy with no signs of excessive leverage. In a still-strong jobs market, consumer incomes are robust. While showing welcome signs of slowing down from an inflation point of view, consumer spending is still solid.

Timely Policy Response

The potential contagion from the failures of SVB and SB in one single weekend was controlled when the U.S. government announced that it would backstop all deposits at the two failed banks. In a similar vein, global contagion was contained the following weekend as the Swiss government intervened to prevent a potential chaotic failure of Credit Suisse.

The Fed also stepped up its liquidity provisions in the wake of the SVB and SB failures. The Fed’s Discount Window borrowing shot past $150 billion in the week ending March 15. The Fed also opened up a Bank Term Funding Program to offer loans of up to one year to depository institutions pledging qualified assets as collateral.

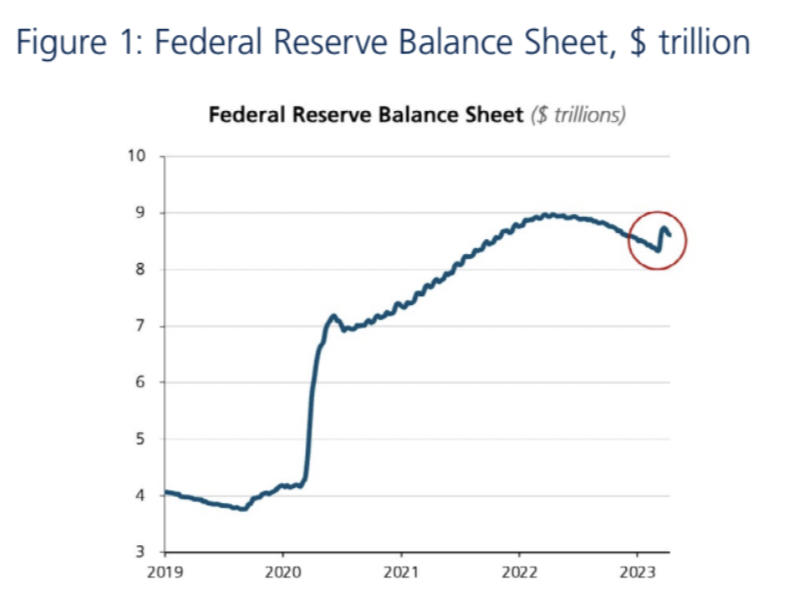

The Fed’s actions have caused its balance sheet to expand in recent weeks as shown in Figure 1.

Source: Federal Reserve

The Fed balance sheet grew to almost $9 trillion in 2022 and had fallen to a low of $8.3 trillion on March 8. The liquidity provisions to mitigate the March banking crisis saw its balance sheet grow again by more than $400 billion.

We believe that the Fed will further expand its balance sheet as needed to ward off a larger scale banking crisis. The additional liquidity will be aimed at stabilization as opposed to an intentional and stimulative increase of the money supply. These funds will help banks preserve or replenish bank capital. They are less likely to be deployed into the real economy in the form of new loans and add to the velocity of money through the multiplier effect.

Banks and Commercial Real Estate

One of the biggest concerns about the current banking situation is the refinancing of commercial real estate (CRE) debt in the near term. The fear of defaults and more bank losses is especially acute for the office segment as excess supply overwhelms lower demand in the new era of remote work.

We know that commercial real estate will be hampered by the higher cost of refinancing as rates have gone higher. We focus on the risks for the sector from the lack of availability of capital, not just the higher cost of capital.

Here are some salient details of the commercial real estate debt market.

- Total commercial real estate debt is around $4.5 trillion

- 38% of this debt is held by banks and thrifts

- However, all commercial real estate debt makes up only 12% of total bank domestic loans

The commercial real estate debt coming due in the next 3 years is almost $1.5 trillion. The office debt maturing in the next 3 years is 12% of that amount or about $180 billion. We observe that both the low share of office debt as a % of total CRE debt and the low share of total CRE debt as a % of all bank loans may limit the impact of office debt defaults more than investors currently fear.

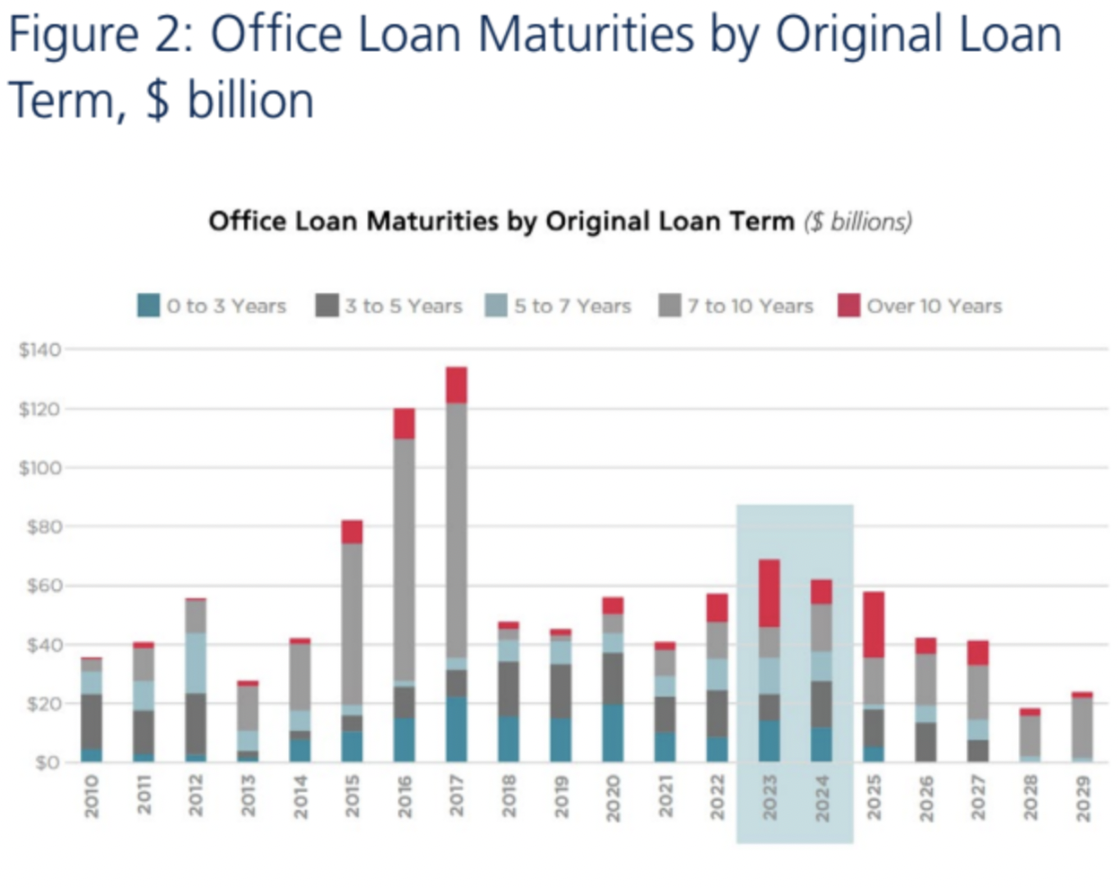

We also point to a more subtle positive observation in the composition of office loans maturing in 2023 and 2024. This is shown in Figure 2.

Source: RCA, Cushman & Wakefield Research

Each bar in Figure 2 breaks down office loans maturing in any given year by the original term loan.It tells us how many of the loans maturing in any year were originated recently (in the last 3 years) and how many loans are more seasoned (over 5 years old).

Let’s take a closer look at just the shaded box in Figure 2 above which highlights office loans maturing in 2023 and 2024. We can see here that most of these maturing loans are seasoned with an original loan term of 5 years or longer.

We believe the original term of loans maturing in the next two years is relevant for the following reason. From the time that these more seasoned loans were originated, the underlying properties had a greater chance to appreciate in value before the onset of higher interest rates. This accrued value appreciation will make refinancing easier even if bank lending standards tighten and loan-to-value ratios come down.

By the same token, the loans most at risk of default would be those that originated recently in the last 3 years. These properties have likely lost value both from non-performance and higher cap rates. On a positive note, they make up a smaller percentage of all office loans maturing in 2023 and 2024.

The cascading impact of the rise in interest rates so far will play out in the commercial real estate market over several months. A likely pause in the Fed tightening cycle will provide welcome relief for all segments of the real estate market.

At this point, we do not see a dire debt crisis stemming from commercial real estate.

Secular Implications

It is inevitable that the end of easy money and the banking crisis of 2023 will leave us with long-term shifts in bank regulations and business models. Here are some quick thoughts on secular changes in regulatory oversight, profitability and valuations.

It is quite likely that we will see greater regulation of regional banks with at least $100 billion in assets. The key lesson from SVB is how to incorporate unrealized losses in banks’ securities portfolios into regulatory capital.

It would also make sense to apply “enhanced prudential standards” to regional banks with assets of more than $100 billion. These standards will subject smaller banks to new stress tests and liquidity rules. We expect bank oversight and scrutiny will become more stringent to assess funding sources and concentration risks. Regulators may also act to deter a run on deposits with additional protection at a greater cost to the banking sector.

The greater burden of regulatory oversight and compliance is likely to bring down profitability and valuations for most financial institutions. The ones who can fundamentally restructure and organize their business models around specific customer needs may be able to avoid this adverse fate.

Economic Impact

Let’s take a step back to see how this micro banking crisis fits into the bigger macro picture for the economy and markets. In that context, it is helpful to recap the latest trends in inflation, jobs and overall growth.

Even as headline inflation continues to decline at a meaningful clip, core inflation has remained largely unchanged in recent months. Unlike the skeptics on this front, we expect shelter costs and wages to also decline gradually in the coming months.

Job growth has slowed down in recent months but still remains healthy with more than 200,000 new jobs created in March. Other metrics of economic activity continue to show a gradual deceleration. We see evidence of an orderly economic slowdown, but no signs of a precipitous and chaotic fall into a deep recession.

At the time of this writing, the contagion from the regional bank crisis in March to the broader U.S. economy seems to be contained. The recent bank failures will likely slow credit growth through tighter lending standards in the coming months. At the margin, this will further slow economic growth.

On the other hand, the “tightening” from slower loan growth will help the Fed pause sooner and pivot to rate cuts earlier than expected. We believe these two effects will offset one another and may well rule out significant changes in the economic outlook.

At this early stage, we do not expect the banking crisis to materially add to the depth of any impending recession.

Summary

The risks which triggered the recent bank failures were unusual and different than those seen in previous crises. We summarize our key takeaways and insights on the topic as follows.

- The current bank crisis arose from duration and liquidity risks which were triggered by a historically rapid run on deposits, not from the more adverse risk of negative credit exposure.

- Timely policy responses have so far contained the regional bank crisis without any material side effects.

- We believe bank regulators and the Fed also have enough policy flexibility going forward to stave off a major systemic shock to the U.S. economy.

- The disinflationary effects of slower loan growth may help the Fed pause and pivot sooner than expected.

- We believe that any potential recession will likely remain short and shallow.

As uncertain as the last few years have been, the events from March add a new dimension of risk to the economic and market outlook. We are even more vigilant, careful and prudent in managing portfolios during these volatile times.

Timely policy responses have so far contained the regional bank crisis.

At this stage, the banking crisis appears to be more of a bump in the road rather than a crippling pothole or crater.

The disinflationary effects of slower loan growth may help the Fed pause and pivot sooner than expected.

From Investments to Family Office to Trustee Services and more, we are your single-source solution.