Efficient tax planning demands a forward-thinking approach, strategically organizing financial affairs to minimize tax liability. An essential element of this approach is the anticipation and understanding of changes in tax laws over time.

The last major overhaul of the tax code came in 2017 when many tax code provisions were changed or added by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, commonly referred to as the TCJA. Most of the TCJA provisions that impact individuals, estates, and pass-through entities will expire or phase out in 2025, an event being referred to as the Great Tax Sunset. However, the TCJA’s biggest change impacting the taxation of C corporations, reducing the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, will not sunset. This means that while the highest individual income tax bracket will increase from 37% to 39.6% after 2025, the C corporation tax rate will not change and will remain at 21%.

The TCJA also introduced the Qualified Business Income deduction, or QBI deduction. This allowed taxpayers to deduct up to 20% of business income from flow-through entities, such as businesses that appear on Schedule C, as well as S corporations and partnerships. The QBI deduction was originally intended to help businesses that were not C corporations compete with the new 21% tax rate for C corporations. The QBI deduction is currently scheduled to be eliminated after 2025.

While it is impossible to predict what tax legislation will be implemented by a future Congress and POTUS, the sunsetting of QBI, the increase of the highest marginal tax rate for individuals, and the continuation of C corporation tax rate makes choosing the appropriate entity for a small business owner less straightforward than it was before 2017.

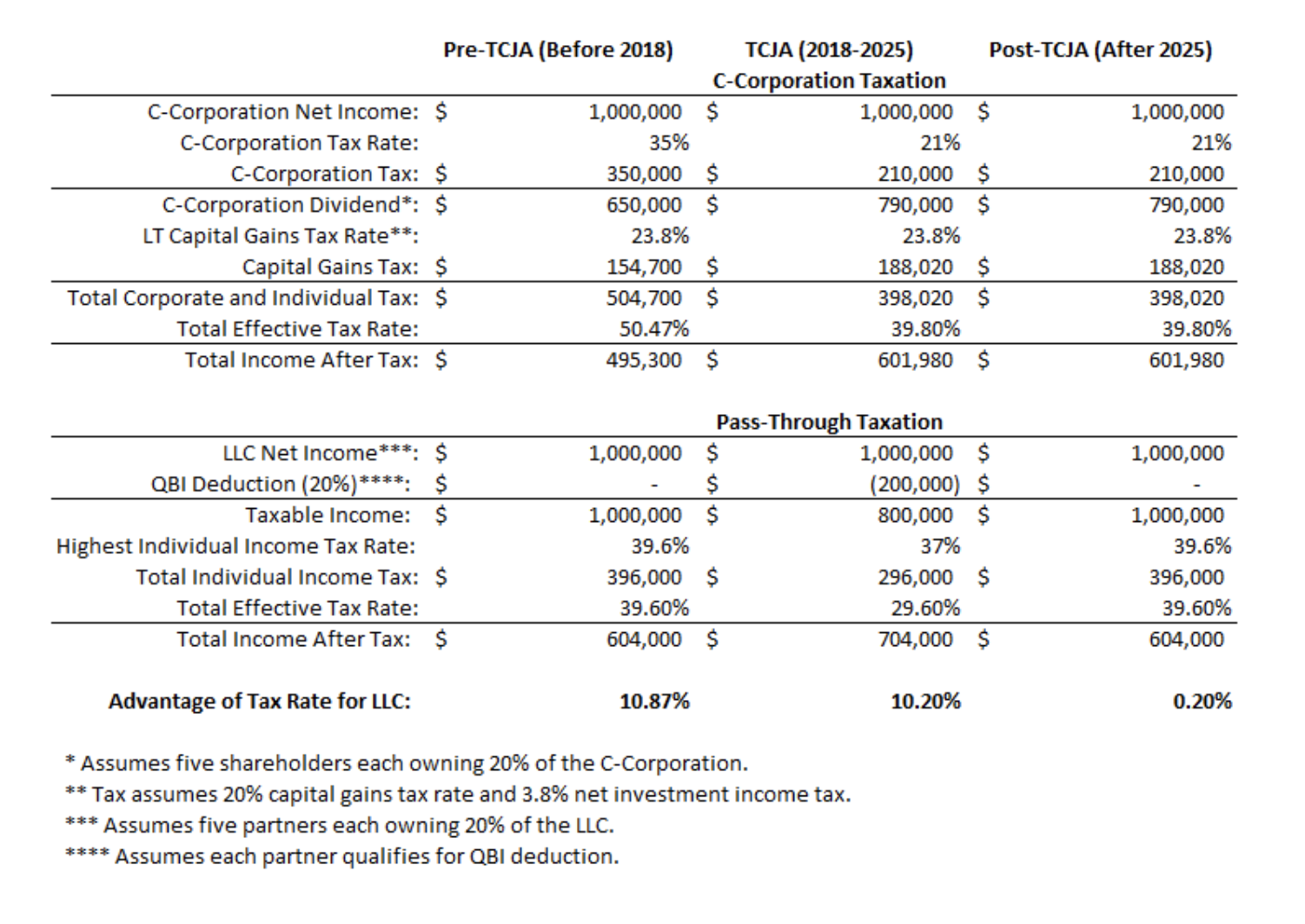

To illustrate, imagine five taxpayers, each owning an equal share of a C corporation doing business in 2017, before the implementation of the TCJA’s modified tax rates. The C corporation has a net income of $1,000,000 and pays 35% income tax, or $350,000. For the sake of simplicity, all remaining income is distributed to the five taxpayers and none of the distribution is considered compensation. The taxpayers pay tax at the highest long-term capital gains tax rate plus net investment income tax on the dividend, or 23.8%. The tax paid by all taxpayers in this example is $504,700, for an overall effective tax rate of 50.47%.

Compare this to the taxation of an LLC owned and operated by five partners with equal ownership. The LLC has a net income of $1,000,000, pays no income tax, and passes the income to its five partners. For the sake of simplicity, all remaining income distributed to the five partners is subject to the highest marginal individual tax rate of 39.6%, and none of the income is considered compensation. The five partners pay a total of $396,000 in tax for an overall effective tax rate of 39.6%. The basic illustration demonstrates why C corporations were seldom used as an entity of choice by small business owners since one level of taxation is considerably lower than two levels of taxation for C corporations.

After the TCJA, C corporation taxation became more appealing as the tax rate was lowered from 35% to 21%. Using the same example above, let’s imagine that the same C corporation doing business in 2018 has a net income of $1,000,000 and pays 21% income tax, or $210,000. The remaining net income is distributed to shareholders who then pay tax at the highest long-term capital gains tax rate plus net investment income tax on the dividend, or 23.8%. The total tax paid by all taxpayers in this example is now $398,020, for an overall effective tax rate of 39.8%. That’s a huge improvement for the two levels of tax for C corporations.

Pass-through owners also had a new advantage under the TCJA with the QBI deduction. As a comparison, the same LLC with a net income of $1,000,000 passes its income to its five partners. Each of the five partners can fully utilize the 20% QBI deduction, which reduces the taxable income from $1,000,000 to $800,000 for all five partners. The five partners pay $296,000 in tax at the highest marginal tax rate for individuals, now lowered to 37%. While C corporation taxation became more appealing, it was still not as appealing as a pass-through entity where individual taxpayers could take a QBI deduction.

However, this is about to change. That same C corporation doing business in 2026, after the Great Tax Sunset will continue to have its $1,000,000 of net income taxed at 21%. Nothing else changes for C corporations in this example, and the total tax paid by all taxpayers is again $398,020, for an overall effective tax rate of 39.8%

The five partners of that same LLC can no longer take advantage of the QBI deduction, which was eliminated in the Great Tax Sunset. Furthermore, the highest marginal tax rate for individuals increased from 37% to 39.6%. The five partners now pay $396,000 in tax for an overall effective tax rate of 39.6%. Suddenly, pass-throughs no longer have the dominant tax advantage they had a few years before.

Lastly, one intriguing side-effect of the corporate tax rate reduction was the renewed interest in the Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion, also referred to as the QSBS exclusion. This tax benefit allows C corporation owners to sell stock without incurring capital gains tax after a statutory period. This additional benefit may tip the balance in favor of C corporations for many small business owners.

Does this mean small business owners should run out and check the box of their LLCs to be treated as C corporations? It is impossible to know what the future holds for tax law changes. While it is not so difficult from a tax perspective to move an LLC treated as a partnership to an LLC treated as a C corporation, it is far more difficult to go back the other way. Nevertheless, if nothing else changes, the analysis of entity choice for small business owners is far more interesting. The Great Tax Sunset will play a significant role in tax planning for several years to come.

From Investments to Family Office to Trustee Services and more, we are your single-source solution.